Today’s teenagers face surmounting pressures in a variety of fields

Maybe there is a reason the 6-year-old games sponsored by the YMCA don’t keep score; maybe it’s to keep the children from perpetuating on the points that are being scored so they can carelessly enjoy playing the game. American society, however, has become preoccupied with scores.

Whether the average sports fan finds Aaron Rodgers throwing his 40th touchdown pass of the year on Sports Center’s Top 10, or the average student finds ACT scores on Harvard’s admissions website, society places high scores on a peadastal. Further, society has pushed a competitive and unrelenting emphasis on scoring upon American youth. Perhaps it’s time to return to the days of YMCA basketball and not to put so much focus on scores.

Although it may be well past the days of intramural first grade basketball, high school has been reduced to 40 yard dash times, bench press max outs, GPAs and SAT scores. However, senior Reed Bowling has conquered these conflicting aspects of high school, focusing to achieve the king of all scores: the 36 on the ACT.

When Bowling found out, he was at swim practice coaching younger children, and he got an unexpected message from his mother.

“I got a text from my mom that said, ‘You better check your ACT score,’” Bowling said.

The rush of relief flooded to Bowling as he found out that his strive for perfection had been accomplished.

When a student wants to go to schools in which the 25th percentile of its application class has an ACT score of 33, every point on the ACT matters. Also, when applying to a school such as MIT, which has an acceptance rate of 7.9 percent, it helps to be one of the 2,000 who achieve perfection on the ACT.

Yet it becomes much easier to strive for perfection when there is a perfect score. In many facets of life, there is no score, yet society has tried to place a numerical representation for it. Whether it be measuring aptitude for college or measuring raw intelligence, some things are not naturally scored, but assigned scores nonetheless.

In addition, the more society progresses into the sports driven structure, the more emphasis it has placed on other scores. Common knowledge has determined that no one can argue with numbers. Society’s trust has been placed in numbers, even though some of these scores, such as the SAT, would not represent a history scholar’s brilliance, or the creativity of a Pulitzer Prize winner.

Even with society’s recent number crunch, senior Adnan Islam remains calm, even as he pursues perfection on the ACT.

“I realized that if you put in time and give it your best shot, then regardless of if you get the best score, you’ll walk out of it happy,” Islam said. “Testing, and in turn any aspect of life, has become too over competitive and stressful once one has forgotten why they’re doing it and what their goal was.”

Islam’s point of view has grown increasingly more uncommon, as stress begins to build inside of American teens’ minds. Perfection has become the standard, and in a world where a difference of just one extra point on the ACT can mean thousands of dollars in scholarships, it has become easy to forget that life is more than a score.

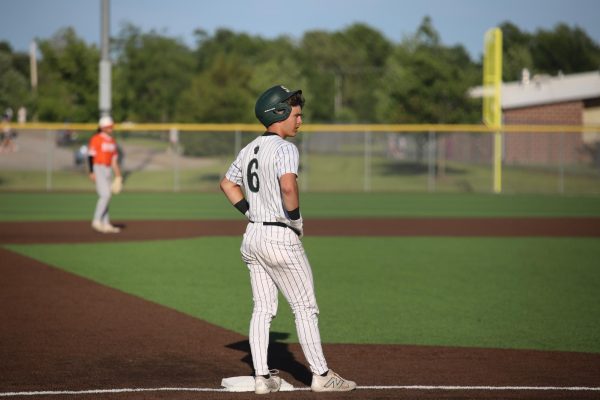

This is not uncommon though, as in other scenarios, life has no longer become about enjoyment and learning. Instead, it has become about practicing relentlessly to perfect a nasty curveball or satisfying any other unrelenting demands of an overly competitive parent.

The hypothetical overly competitive parent, for some, never seems to appear, but state champion swimmer Gabbi Miller sees it all too often.

“A lot of parents get really into it,” Miller said. “They become the second coach, as they say ‘You did all of this wrong’ and that ‘It’s ruining your future.’”

Not only is the competitive fervor in the parents, but the coaches also participate in screaming and overreactions to simple mistakes made by athletes. This has come with the transition of society, from the days where organized sports started in third grade, to skipping the days of YMCA and jumping to elaborate traveling sports teams that cost parents thousands. In combination with the increased marketability of professional athletes, parents and coaches expect their athlete to be the “next big thing.”

However, this over-competitiveness has flooded into society, taking personal enjoyment out of many aspects of life. The trend of over-competitiveness has shifted into education too, as parents are constantly pressuring teens to achieve highly. In a 2011 study conducted by the Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, over one third of students who were polled said getting into a good college was more important than being a good person. Although that may not be completely parental pressure, of that same group, over half of the students said acceptance to a good college was more important to their parents than being a good person.

However, when societal and parental pressure combine to force a loss of focus in today’s youth, it is a true tragedy and must be fixed immediately.

“When there’s an activity that you used to enjoy, it becomes too competitive when you do it just to win,” Islam said. “It becomes overly competitive when you lose sight of why you’re doing an activity in favor of just trying to beat other people.”

In its simplest terms, winning in most competitions is defined by scoring more points than the opponent. Whether it is through sports, or through testing, the goal has always been to score as many points as possible so that one can win. However, in a scenario as complex and unpredictable as life, there is no winning and losing, and there is no purpose to an activity when it is simply to beat other people. Instead of attempting to count up meaningless points, there is something to be said for enjoying life and being the best overall person one can be, even though there might not be a score to measure how well one has done.