Students and staff share experiences and analysis of racism at Southwest

On Aug. 9, 2014, an unarmed, black teenage boy was shot and killed by a white police officer in Ferguson, Mo. An international turmoil began, with many citizens and leaders from various states and countries condemning the shooter, Darren Wilson, for the racist and wrongful death of Michael Brown.

Yet the halls and classrooms of Blue Valley Southwest have remained quiet about this tragedy. Conversations at the lunch tables and in the library did not turn toward the event, even as television screens displayed updates on the situation. No moment of silence or remembrance was held over the announcements, despite Aug. 14, the first day of school, being declared a National Moment of Silence for the increase of police brutality in the United States.

Even as I considered writing an article on the situation at Ferguson, I had to reject the idea, because the reality of the situation was that no one cared enough about Brown’s death to read about it.

People at Southwest and in the surrounding area wanted to believe that Johnson County was separate from Ferguson, that racism wasn’t a problem in Blue Valley and that ignoring issues going on elsewhere would make them go away. Admittedly, it’s tempting to use our privilege as an affluent community to ignore the inequality that occurs around the world. But not only does this hurt people suffering in other places, it also affects those in our own community who endure the same problems.

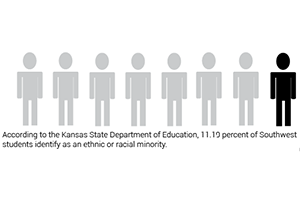

“People want to be like, ‘Racism is over; stereotyping isn’t here; it’ll only go away if people stop talking about it,’” sophomore Niya McAdoo, who identifies as mixed race, said. “That makes it worse. I hear a lot of the time, ‘Oh, Southwest is diverse; we have all of this culture,’ and whatnot, and I look around, and I’m like, we actually don’t. We don’t have a lot of that at all.”

In fact, instances of racism at Southwest are much more common than our predominantly white school would like to believe.

“Students will say stuff that is kind of offensive sometimes, and they say it in a way that you know that they’re joking, so you don’t really make a big deal out of it,” Pakistani junior Adnan Islam said. “But it’s still offensive.”

African-American senior Romaric Keuwo has been the target of jokes calling him “Oreo,” implying that he is black on the outside and white on the inside. He has also been called a very “white” black person.

“Because I don’t talk, like, ‘yo, yo, yo,’ and that kind of stuff, does it make me less black or less African-American?” Keuwo said. “No, no it does not. I’ll try to laugh at it, and I know that it’s a joke, but honestly, it bothers me.”

Keuwo’s experience reveals one of the primary causes of racist actions at Southwest: stereotypes. Living in Johnson County, an area very sheltered from the outside world, it is often difficult for students to contradict what they have heard about different groups of people when meeting those people in reality.

“There are jokes and stereotypes ingrained in our culture that come up all the time, and they’re just so common,” Islam said. “I think [the problem is] the students and what they’re exposed to at school with other students and the media.”

In 2011, when terrorist Osama bin Laden was killed by American forces, Middle Eastern students experienced an increase in racial bullying. Persian senior Parisa Hemmat had students joke that bin Laden was her grandfather, implying that because she was Middle Eastern, she was related to the terrorist.

“One person was like, ‘You don’t belong here — go back to your country,’” Hemmat said.

The bullying Hemmat endured was not an isolated incident. Other Middle Eastern students were targeted by other students comparing them to terrorists.

“I’m Middle Eastern, so kids will make bomb jokes or jokes about me flying planes into stuff,” Islam said. “I’ve heard it so many times that each instance doesn’t offend me, but the fact that it happens so much, overall, just makes me think about how stereotypes are so prevalent that people almost begin to think of them as true. And they get normalized, and people take it as a joke, but deep down, I don’t know if it’s a joke or not.”

Students, however, are not the only ones perpetuating racism at Southwest.

“I remember freshman year, my parents came in to the parent-teacher conference,” McAdoo said. “I remember my teacher told them that when she first saw me walk in the room, she automatically, right off the bat, just because of the way I looked, assumed that I was going to be her worst problem in that class. She told my parents that.”

At another conference, McAdoo was walking around with her one and three-year-old sisters as her parents talked with a teacher. The next day, a student told her that his mother had assumed McAdoo’s sisters were her daughters, an assumption that stems from the oversexualization of black teenage girls.

“At the end of the day, even if I did have kids, it’s not your place or your business to judge me at all, in any type of way,” McAdoo said.

In its five years as a school, Southwest has still managed to maintain an image of equality for all its students. However, it is obvious that this assumption is not entirely accurate.

“You know how we always say we’re one family?” South Korean senior Jae Young Jeong said. “If you discriminate against other people and have low respect for them, then that’s all a lie. We’re not one if you don’t actually try to be one.”

Part of the problem stems from Johnson County residents’ tendency to prize political correctness over recognition of racial issues in the area. People of all ages — even adults — are more apt to ignore the presence of racism in favor of throwing around phrases like “post-racial America” and “color blind.”

“Sometimes people will say, ‘I don’t really see color,’” counselor Kristi Dixon said. “And that’s like, well, are you looking with eyes open, or are you covering up your face? I feel like I understand the sentiment when people say that; they’re trying to say, ‘I don’t judge you based on your race,’ which is great. I appreciate that. I try to do the same. But to completely disregard [race] is hurtful … I would like people to recognize that race exists and that racism exists. Because to pretend that it doesn’t gives all the power to the bad guys.”

The question remains: what can students and staff do to absolve racism at our school? First and foremost, it needs to be recognized that the problem exists. I chose to write this piece because I knew racism existed, but each time I interviewed a student about their experiences, my eyes were opened to new levels of harassment based on race, and I know that I still have a lot to learn. As a white journalist, I was blinded by my privilege, which ensures that I will never face racism. Naivete is a luxury that we all must leave behind in order to surpass judgment, stereotypes, and harassment on the basis of race.

Secondly, it is necessary that Southwest as a whole takes steps to combat the racism that still seeps through the cracks. This means stepping in when witnessing a racist joke or statement by others, listening to people of color about what is and is not appropriate in order to actively learn about different ways we could be perpetuating racism and constantly self-assessing our actions to make sure we are making our school a safe place for all students and staff.

Finally, we must embrace the different backgrounds and experiences of our peers.

“Sometimes I get looks, like, ‘Why are you wearing such foreign clothing?’” Keuwo said. “It’s almost that kind of look, but they never say it. And it’s like, ‘What are you looking at? Why does it matter to you?’ I love to show off my culture. I love my culture.”

Keuwo and all other students and staff deserve to have their cultures, religions and races respected and acknowledged.

“You have the right to feel safe here,” Dixon said. “You have the right to expect that people not say hateful, hurtful things. Nobody deserves to have their voice stolen or silenced.”

Madison is a first-year staff writer for the Standard, and spends her work time writing articles or doodling in the margins of her official newspaper notebook....